In January, the consumer watchdog group U.S. PIRG Education Fund released a report about the state of the right to repair, and celebrated significant progress by the Digital Right to Repair Coalition over the last decade.

In particular, the report asserts that model right-to-repair legislation has been filed hundreds of times in nearly every state, and highlights the passage of repair laws by seven states.1

Authors: Christopher R. Brennan Gerard M. Donovan

While supporters may seek to introduce model legislation, current enacted state laws are not a model of consistency. They vary in nearly all dimensions, including the scope of covered products, the mechanisms by which access is provided or permitted, and the protections afforded to the original manufacturers of the covered products.

We see the right to repair movement at a tipping point. Buoyed by recent progress, the coalition behind these repair laws will continue to push for adoption by more states. But as this patchwork of state laws takes hold, what are the practical consequences for national and international manufacturers?

And how can these laws be squared with well-established intellectual property rights that incentivize innovation and competition laws that promote greater consumer welfare through competition on the merits and eschew free-riding?

This article shines light on a growing thicket of state repair laws and the looming struggle for rightsholders and courts that must grapple with their varied requirements.

A Brief Overview of Repair Laws in the U.S.

The current repair movement traces back to the emerging prevalence of software-enabled devices in the early 2000s. Yet more than a decade would pass before Massachusetts enacted a 2012 law regarding access by independent auto shops to original equipment manufacturer dealers' diagnostic and repair information.2

Since then, the Digital Right to Repair Coalition has largely pursued a legislative and regulatory strategy focused on influencing federal and state governments and relevant agencies, e.g., the Federal Trade Commission and the U.S. Copyright Office, to compel access to repair information and exempt efforts to acquire that access from the prohibitions of other laws, such as the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

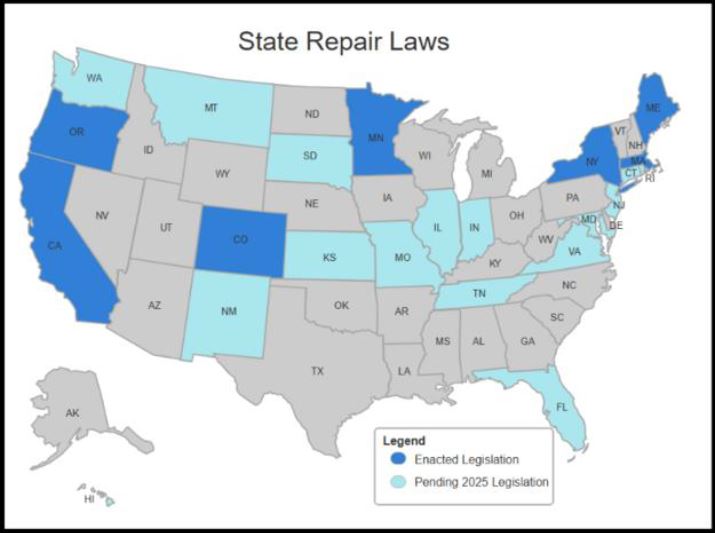

This lobbying has produced mixed results in the last 12 years. Perennial efforts for a federal repair law have failed to gain traction in Congress, even when supported by bipartisan sponsors. In contrast, states have proven more fertile ground. The following map reflects enacted state repair laws and states where repair legislation has been introduced for the 2025 legislative session.

We note two observations on the current distribution of state repair laws.

First, success to date has largely been confined to Democratic-leaning state legislatures. That is unsurprising, given the Biden administration's embrace of expanded repair rights under a broader attack on perceived corporate concentration. It remains to be seen whether repair advocates can retool their message under an America First banner for draft bills introduced in Florida, Missouri and other Republican-controlled states.

Second, the Digital Right to Repair Coalition need not win every state, or even a majority of states, to compel nationwide changes. Recall how California has been setting itsown automotive emission standards for decades, driving automakers to build compliant vehicle platforms regardless of more lenient laws across their broader customer base.3

With repair laws already on the books in California and New York, affected stakeholders — including courts, rightsholders and the public — must consider how this growing body of law will alter the legal and economic incentives that drive innovation, brand goodwill and product lifecycle management.

Tensions With Traditional Intellectual Property and Competition Principles

In general, existing state repair laws appear to prioritize repair information access and compelled disclosures by original equipment manufacturers without sufficient clarity for how those provisions should be moderated by OEMs' preexisting intellectual property rights.

For example, Colorado's repair law, effective Jan. 1, 2026, is likely the broadest repair law enacted to date.4 In regard to digital electronic equipment, it mandates the following:

A manufacturer shall make available to an independent repair provider or owner, on fair and reasonable terms, any documentation, embedded software, tool, part, or other device or implement that the manufacturer provides for effecting the services of maintenance, repair, or diagnosis on the manufacturer's digital electronic equipment.

This language appears intended to throw the OEM's toolbox wide open. But Colorado's law excludes many types of products5 and comes with several conditional limitations for those not exempted.

In particular, the law says it does not apply to conduct that would divulge a trade secret, but the manufacturer cannot claim that the documentation, part, embedded software, embedded software for agricultural equipment, firmware, tool, or, with owner authorization, data itself is a trade secret.6 Similarly, nothing requires an OEM to license any intellectual property, unless "such licensing is necessary for providing services."

Setting aside, for the moment, difficulties in harmonizing these provisions, such laws likely conflict with OEMs' well-established right to control, and even exclude access to, their intellectual property.

Intellectual property laws promote innovation by rewarding the innovators with exclusive rights to their developments, with varying restrictions on those exclusive rights depending on the type of intellectual property developed.

Consider an OEM that developed a proprietary software tool to diagnose potential hardware faults using a trade secret algorithm created from historical repair data.

Intellectual property rights under both federal and state law would entitle that OEM to reserve that tool for their in-house technicians or to license the tool to an affiliate that was contractually obligated to follow agreed-to quality and safety standards and to not disclose or license the tool to others.

The secrecy of such a tool could provide the OEM with significant value, and thus warrant trade secret protection under state and federal laws provided the OEM takes reasonable measures to keep it secret.

Yet an OEM that refuses to provide its trade secret information to potential competitors could face allegations that its exercise of its IP rights violates Colorado's and other states' repair laws.

The issues can become more complex for OEMs that license intellectual property from others for their products and, as such, may lack rights to disclose information that state repair laws may require.

Additionally, these state repair laws may undermine key aspects of federal antitrust jurisprudence. Under settled U.S. Supreme Court precedent, there is generally no duty to deal with others, especially rivals.

While a narrow exemption may arise for natural monopolies that can be deemed essential facilities, antitrust law prefers rivals to compete on the merits and improve consumer choice through innovation.

Similarly, antitrust law discourages courts from acting as a central planner that sets the terms upon which rivals should deal.

Can an alleged violation of a state's repair law serve as evidence of exclusionary conduct under the antitrust laws? Conversely, does compliance with a state repair law bar a finding of monopoly power in an alleged aftermarket?

On these and other issues, state repair laws threaten to upset the delicate balance between the rewards of innovation and the desire for robust, competitive markets.

The foregoing concerns are not academic. Massachusetts' repair law relating to vehicle telemetry data resulted in four years of federal litigation over alleged conflicts with the Clean Air Act or federal automotive safety standards issued under the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act.7 We expect such litigation to increase, especially where state laws provide for a private right of action against OEMs.

The Growing Thicket of State Repair Laws

The impact of state repair laws will extend beyond OEMs' legal departments. For nearly all covered products, OEMs develop products for national or global markets. Customers in Maine receive the same smartwatch as do customers in California. Ancillary operations — e.g., product support, spare parts, IP policies and licensing strategies — are similarly standardized.

State repair laws do not follow suit. As previously mentioned, existing laws vary dramatically and there is no reason to believe the political forces that drive these variations will not apply in other states.

By way of example, only Colorado's repair law applies to farm equipment, while only Maine and Massachusetts' laws address automotive data. One state may allow certain costs to be charged by OEMs for access to software tools, while another state may prohibit that charge. One state may recognize limitations on information that creates a safety risk for consumers or repairers, while another state's law may be silent on the issue.

In response, OEMs should proactively consider their compliance strategy. Proactive assessment of information and tools that are necessary for repair versus those that make repair more efficient or easier and evaluation of information and tools that are trade secrets versus those that may be provided to others will assist with compliance.

Some OEMs may also choose to proactively make certain information available to the public, or at least to noncommercial repairers, in attempts to garner goodwill with those in the right to repair movement and potentially mitigate risk of state repair laws specifically targeting their industries.

Others may choose to increase their lobbying efforts in relevant forums or to proactively challenge enacted laws based on their potential conflicts with federal laws.

And while the repair laws create risks to OEM's intellectual property, they may also provide new rights to competitors' information that were traditionally safeguarded by principles of both intellectual property and competition law. While strategies may vary, the growing scope of repair laws makes it likely that most OEMs will be touched by them in the coming years.

Conclusion

In sum, the emergence of state repair laws is quickly becoming a thicket of uncertain and inconsistent obligations. Manufacturers should not wait to audit their current practices and determine the best long-term solutions for their products and customers.

Such planning also may flag grounds for legal challenges and minimize the potential for rival third-party repairs to weaponize state repair laws through alleged violations. At the very least, an active, assertive response will minimize the likelihood that state repair laws result in more breaks than fixes for affected manufacturers.

The opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of their employer, its clients, or Portfolio Media Inc., or any of its or their respective affiliates. This article is for general information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice.

- U.S. PIRG Education Fund, The State of Right to Repair (2025).

- An Act Protecting Motor Vehicle Owners and Small Businesses in Repairing Motor Vehicles, 2012 Mass. Acts 241.

- See, e.g., Justices Preserve Calif. Vehicle Emissions Autonomy, Law360 (Dec. 16, 2024).

- Consumer Right to Repair Digital Electronic Equipment, H.B. 1121, 74th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Colo. 2024).

- For example, Colorado's exemptions include, but are not limited to, video game consoles, medical devices, and motor vehicles. See Id. at Section 6-1-1503(5).

- See Id. at Section 6-1-1503(2)(A).

- Mass. Auto Telematics Data Law Not Preempted, Judge Says, Law360 (Feb. 18, 2025).